Understanding flues and chimneys is crucial for anyone maintaining or upgrading their home heating system. In simple terms, the flue is the working part of a chimney, the passage that safely carries combustion gases (smoke, fumes) out of the home, while the chimney is the structure housing that flue. Traditional British houses often feature brick chimneys rising above the roofline; however, modern installations utilise a variety of flue systems. Whether you’re a homeowner seeking to understand your fireplace or a tradesperson planning a stove installation, a solid grasp of flue and chimney types will help you ensure your heating system is both effective and compliant.

Traditional Chimney Systems

Masonry Chimneys (Class 1): For centuries, homes in the UK have been built with masonry chimneys constructed of brick or stone. These traditional chimneys vent open fireplaces and solid-fuel stoves, relying on natural draft (hot air rising) to pull smoke upward. A classic brick chimney has a relatively large cross-section flue (often 7–9 inches in diameter for older types) suitable for an open wood or coal fire. Many Class 1 chimneys in homes built before the late 1960s were unlined brick, but from the mid-20th century onwards, it became common to line new chimneys with fireclay or concrete liners for improved safety and durability.

You can usually identify a Class 1 chimney by its substantial chimney stack and pot on the roof, as well as a traditional open fireplace or stove connection at the hearth. These robust chimneys can withstand the high heat and soot generated by wood-burning. However, older unlined chimneys often require relining with a stainless steel liner when fitting a modern stove, both to ensure the flue is gas-tight and appropriately sized for the appliance. Lining an ageing chimney improves efficiency and safety, preventing smoke leakage through bricks and providing a smooth flue for better draft.

Pre-Fabricated Metal Flues: In the mid-late 20th century, as alternatives to bulky masonry chimneys, some houses were built with prefabricated flue systems. These consist of an interlocking double-walled metal flue pipe running up through the house (often boxed in) and terminating in a metal cowl on the roof instead of a brick stack. Pre-fabricated flues typically are 5-inch (125 mm) diameter metal pipes, a size sufficient for most gas fires and some slim appliances.

They are often identified by a metal chimney cowl or a short metal pipe visible on the roof, sometimes poking through a small false chimney pot. Older pre-fab systems can be Class 2 (for gas only, around 125 mm) or occasionally Class 1 (larger 7-inch versions for solid fuel), but most serve gas fires or room heaters. They function like any chimney, using the heated air’s natural rise to pull exhaust gases up, but have metal flue walls and must be kept in good condition, as corrosion can be an issue over decades. Prefabricated flues enable the installation of fireplaces in homes without the need for a full masonry chimney.

Pre-Cast Flue Block Systems: Since the 1960s and 1970s, many UK builders have utilised pre-cast concrete flue blocks in new homes, particularly for gas fires. These Class 2 flue systems are made of interlocking concrete blocks that form a rectangular flue passage (often nicknamed “letterbox” flues).

Built into the interior walls, usually the chimney breast, of modern homes, pre-cast flues are shallow and narrow. You might spot their presence by a raised ridge vent or slim metal flue terminal on the roof rather than a full chimney stack.

Pre-cast flue blocks typically accommodate only slim-line gas fires; their small cross-section cannot vent solid fuel fires or deeper open gas fires without modifications. Spacer kits or a fireplace recess might allow a slightly deeper gas appliance, but solid fuel stoves usually cannot be used with pre-cast flues. The concrete flue blocks are modular in size (like masonry blocks) and integrate easily into walls, making them a popular and economical choice in late 20th-century construction.

Modern Flue and Chimney Systems

In recent years, chimney technology has evolved, and many homes now use factory-made insulated flue systems or innovative chimney liners instead of traditional brick stacks. Modern systems are often easier to install, highly efficient at retaining heat, and specifically tailored to the type of fuel used.

Insulated Twin-Wall Chimneys: A very common modern solution for homes without an existing chimney (or extensions and new additions) is the twin-wall stainless steel chimney system. These factory-made system chimneys consist of concentric stainless steel pipes, an inner flue pipe and an outer casing, with insulation filling the space between them. The insulation, typically mineral wool, keeps flue gases hot, improving draft and preventing condensate.

Twin-wall systems are modular, available in various lengths, and include elbows, tees, support brackets, and terminals that lock or twist together for quick assembly. They can be run internally (through floors and ceilings with fire-safe enclosures) or externally up an outside wall.

Unlike masonry, a twin-wall metal chimney does not require a foundation, making it ideal for retrofitting a wood-burning stove into a home with no existing chimney. Modern standards (BS EN 1856-1) certify these systems for solid fuel use, and building regs allow twin-wall chimneys to pass through floors or even be used to reline a larger chimney if needed.

Their sleek steel appearance, often powder-coated in black or left in its natural silver finish, is a visible sign of a contemporary stove installation. For safety, always maintain the required air gap to combustibles specified by the manufacturer (typically 50 mm or more), and only use certified twin-wall components – it’s actually illegal to install non-approved flue sections.

Ceramic and Pumice Modular Chimneys: Alongside metal flues, engineered masonry chimney systems have developed. Pumice chimney systems use volcanic pumice aggregate, a natural insulator, formed into lightweight blocks or double-walled chimney units. These systems (e.g. the double-module pumice blocks) exploit pumice’s insulation so well that no extra insulation is needed around the flue.

They are assembled block by block, featuring an inner liner and outer casing, which gives them the appearance of a traditional chimney but with modern performance. Pumice systems are suitable for wood, multi-fuel, oil or gas, but not for condensing appliances, as they must stay dry inside.

They are most often used in new construction, as they require a concrete foundation, similar to a masonry chimney, and are built by a bricklayer.

Ceramic chimney systems are another high-end modern option: they feature an inner ceramic liner, which is very durable and acid-resistant, wrapped in insulation and encased in precast blocks. These can even handle condensing boilers in some cases. Both pumice and ceramic systems meet strict standards (BS EN 1858 and BS EN 13063, respectively) and offer long life and excellent heat retention, helping flue gases stay warm for a good draw. While typically seen in new builds, they can be retrofitted inside existing large chimneys or structures, albeit with more construction work.

Balanced Flue Systems for Gas: Not all fires need a conventional vertical flue. Modern balanced flue systems are designed to accommodate room-sealed gas appliances. A balanced flue is a twin-wall pipe with a concentric design, where the inner pipe carries exhaust gases out while the outer pipe draws fresh outside air in for combustion.

The appliance (gas stove or fire) is completely sealed from the room, so it draws no room air and expels no fumes indoors.

Balanced flue gas fires can be vented horizontally through an external wall or vertically through the roof, giving great flexibility in homes without any chimney. Many glass-fronted gas stoves and modern gas fires are available in balanced flue versions, such as the Infinity 890BF.

The installation involves cutting a hole through an outside wall for the flue terminal or running the twin-pipe up through the roof space. The beauty of a balanced flue is its safety and efficiency. Because the system is sealed and uses outdoor air, there are no drafts in the room.

Homeowners also like that no tall chimney structure is needed; the flue terminal is typically a neat vent or pipe on the exterior.

Of course, balanced flue appliances must be specially designed for this system, you cannot simply attach a balanced flue pipe to a conventional gas fire. When installing any gas fire or stove, Gas Safe regulations apply, and balanced flues are no exception: correct placement of the terminal (clear of windows, eaves, etc.) is critical.

Flueless and Power-Flue Appliances: As a side note, there are also flueless gas fires on the market, which use a catalytic converter to clean the combustion gases, allowing them to be released into the room. Flueless appliances require no chimney at all, but they do require excellent ventilation, an air vent in the room, and are limited in heat output. Similarly, power flue (fan-assisted) gas fires exist, which use an electrically powered fan to force flue gases out through a wall vent.

These are typically used for decorative gas fires, especially open-fronted ones, where a natural draft chimney is not available or insufficient. A power flue still expels gases outside, so it’s not flueless, but it doesn’t rely on natural upward convection; the fan can even allow a horizontal flue run out the wall. Power flue units aren’t common for wood-burning stoves, but they are another modern tool to solve chimney drafting problems or allow fireplaces in challenging locations.

For completeness, plastic flue pipes are also used today, but only for low-temperature condensing boilers (never for stoves or fires). Building regulations permit certain high-grade plastics to be used in venting boilers because the exhaust temperatures are very low; all solid-fuel and gas fires, however, use metal or ceramic flue systems due to the high heat.

Chimney Liners and Upgrades:

Whether you have an old chimney or a new flue, liners play a crucial role in safety and performance. A chimney liner is a specifically designed flue conduit placed inside a chimney or flue route. In traditional chimneys, liners protect the masonry and contain the smoke; in new systems, the liner is the flue (as in twin-wall or pumice systems).

Clay, Concrete, and Pumice Liners: Many brick chimneys built in the last 50–60 years include clay/ceramic liners, fireclay sections that form a smooth, heat-resistant flue internally. Clay liners are still used in on-site built chimneys, classified as “custom built” chimneys, and come in round or square profiles of various sizes.

They are excellent for longevity and can handle all fuels (wood, coal, oil, and gas) as long as the flue gases stay above the dew point (they are designed for dry operation under BS EN 1457).

Alternatively, concrete flue liners, often made of pumice-concrete mixtures, have also been used; these are heavy sections that are stacked inside a new chimney. Pumice liners are popular because pumice is a natural insulator, helping keep flue gas temperatures up. When relining an existing chimney with clay or concrete liners, typically you install them by breaking into the chimney and lowering sections down, then backfilling around with insulating mortar – a labour-intensive job. Importantly, any liner must be appropriate for the appliance.

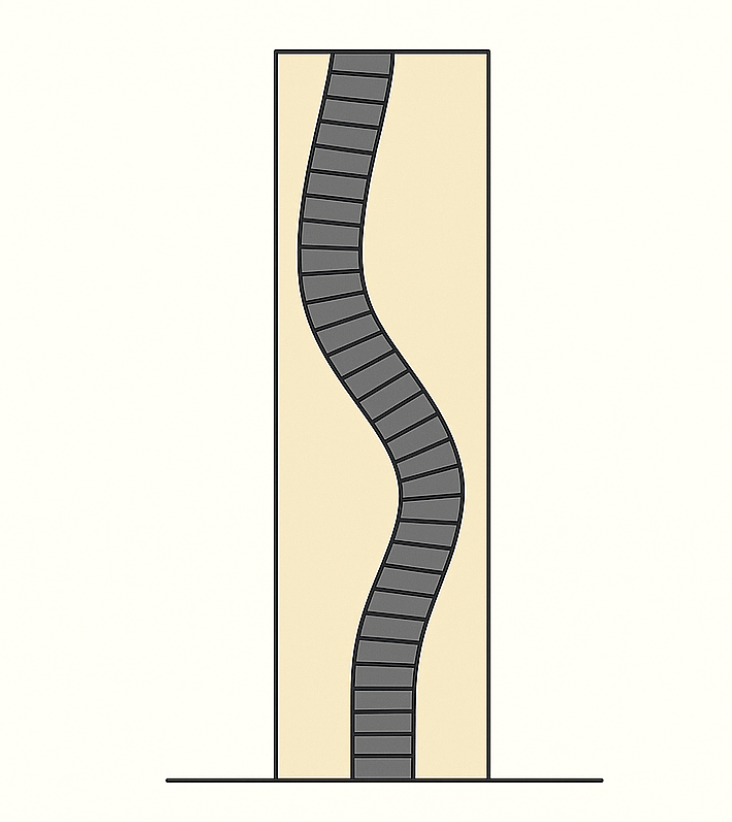

Stainless Steel Flexible Liners: Perhaps the most common retrofit today is the flexible stainless steel liner for chimneys. These liners are used to reline existing chimney flues, especially when installing wood-burning or multi-fuel stoves into old fireplaces. A flexible liner is essentially a continuous metal tube, made of high-grade stainless steel, that is lowered down an existing chimney. Twin-skin flexible liners, with two layers of overlapping steel, often corrugated, are rated for wood and multi-fuel use, whereas single-skin liners are for gas only.

It’s critical never to use a single-skin (gas-rated) liner on a solid fuel stove, as it will deteriorate quickly and could even burst. Flexible liners are certified to BS EN 1856-2 and must be installed with the correct support and terminals to be considered a “system”. When selecting a liner, diameter matters: UK regulations (Document J) generally require a minimum 150 mm (6 inch) flue diameter for wood-burning stoves, with a concession for certain clean-burning (DEFRA-exempt) stoves that may use 125 mm (5 inch) if the manufacturer permits.

In practice, many wood-burning stove installers will drop a 6″ stainless liner down an old 9″ chimney to ensure a good, tight flue that matches the stove outlet. This improves draft, keeps the smoke velocity up, and prevents excessive cooling and soot deposit in the oversized old shaft. Flexible liners have made it far easier to bring old chimneys up to modern standards, provided the chimney is clear and straight enough to accommodate the liner. Once in place, the top is sealed with a register plate or top plate and usually fitted with a rain cap or pot hanging cowl.

Connecting Flue Pipes: Lastly, remember that from your appliance to the chimney or flue proper, you will have a connecting flue pipe. For a stove, this refers to the visible stovepipe rising from the appliance. These pipes are typically vitreous enamelled steel or stainless steel and are single-walled; they should only be used in the room up to where the flue/chimney continues, e.g. to the ceiling or chimney entry. Stove pipes get very hot and require clearance from combustibles, but they provide the crucial link between the appliance and the chimney.

Modern standards even allow the use of insulated twin-wall chimney sections as the connecting flue pipe, if needed, for instance, when running an insulated pipe straight from the stove through an exterior wall. Always follow the manufacturer’s guidance for connecting pipe diameter. Never reduce it below the stove’s outlet size, and ensure that at least the first 600 mm of rise is vertical off the stove for a good draft before any bends.

Wood-Burning Stoves and Their Flues:

Wood-burning and multi-fuel stoves have surged in popularity as efficient heating appliances, but they place particular demands on flue systems. Solid fuel appliances produce smoke, soot, and creosote, and operate at high temperatures; therefore, the flue must be up to the task.

When installing a stove into an existing chimney, check the chimney’s condition and size. Large old chimneys for open fires can be inefficient for a closed stove; the volume is too great, leading to cooling of the smoke.

This causes creosote deposits and weak draft. Lining with a properly sized stainless steel liner helps the stove perform efficiently and safely. Approved Document J generally calls for a 150 mm flue for most stoves, ensuring the cross-sectional area isn’t too small or too large for the stove’s requirements. An “oversized” flue can be almost as problematic as an undersized one, if the flue is much wider than the stove outlet, smoke expands and cools, slowing the up-draft.

Conversely, an undersized flue will restrict the appliance’s airflow. So, the best practice is to match the flue diameter to the stove outlet (or follow the appliance manufacturer’s specified flue size). Modern stoves typically have either a 5″ or 6″ outlet; many DEFRA-compliant models use 5″ and can go into a 5″ liner, but non-DEFRA stoves usually need 6″. Always double-check the requirements.

Maintaining flue temperature is vital for wood stoves. If the smoke cools too much in the chimney, water and tar will condense. That’s why insulation, either inherent, as in twin-wall or pumice systems, or added by backfilling around liners, is important; it keeps flue gases in the optimal 150–450°C range for clean flow. Slumbering a stove, burning slowly overnight, or burning wet/green wood will cause low flue temperatures, leading to heavy condensation and tar accumulation. This tar is essentially creosote, a highly flammable, dark deposit.

Tar build-up is one of the most common issues in wood-burning chimneys and a primary cause of chimney fires. Burning wood with too little air or using damp fuel produces excessive soot and corrosive deposits, which can ignite or eat away at metal flue liners. Thus, using properly seasoned dry wood and operating the stove with sufficient air supply (avoiding long periods of smouldering) are key to minimising creosote. Modern Ecodesign stoves are cleaner-burning, but still require good flue conditions to avoid problems.

For wood-burning stoves, regular sweeping and maintenance of the chimney are crucial. We recommend having the chimney swept at least three times a year when burning wood regularly, typically once at the start of the heating season, once mid-season and once before the end of the season. In less frequently used installations, an annual sweep may suffice, but check for soot buildup. Sweeping removes the soot and tar that could impede flow or catch fire. As one stove manufacturer’s expert notes, soot and tar accumulation reduce the flue’s draw and make the stove run less efficiently, while increasing the risk of a chimney fire. A clean flue allows your stove to breathe freely and burn efficiently.

Another consideration is ventilation: wood stoves above a certain size require an air vent in the room (Document J mandates adequate combustion air). If your home is modern and airtight, a dedicated external air supply to the stove might be needed to prevent the stove from drawing air down the chimney or from elsewhere. All solid-fuel stove installations in the UK must also include a carbon monoxide alarm in the same room, as per building regulations, a critical safety feature given the risk if flues are blocked or malfunctioning.

Gas Fires and Flue Considerations:

Gas appliances, whether traditional gas fires or modern gas stoves, have their own set of flue requirements. Traditional open-fronted gas fires often used the same chimneys as coal fires (Class 1 chimneys). If you have a Class 1 brick chimney, it can generally accommodate either gas or solid fuel, it’s the most versatile, though do ensure the chimney is lined or in good condition for gas, to prevent condensation leakage.

Many gas fires in older homes simply vent up the masonry chimney. These should be checked periodically for obstructions, even if gas burns “clean”, a chimney can still get bird nests or debris. Gas produces moisture when burned, so unlined brick chimneys can develop condensation stains if the gas fumes cool and condense in the flue – a reason many opt to line chimneys for gas fires as well.

In more modern homes with Class 2 flue systems (like a 5″ prefab or a pre-cast flue), you are typically limited to certain gas appliances. A Class 2 flue (125 mm) can safely vent gas fires or gas stoves that are designed for that flue size, as well as decorative fuel-effect fires and balanced-flue appliances. For instance, most gas stoves on the UK market have options for Class 2 installation; they are engineered to work with the smaller flue. However, you could not, for example, put a large open gas log fire (which would need a Class 1 chimney) on a pre-cast flue. Gas flue blocks (pre-cast) specifically are only for gas fires of the slim, inset type.

Balanced flue gas fires, as mentioned, don’t use internal house air or chimneys at all, which is a big advantage in homes without a chimney. They are room-sealed and typically more efficient than open flue gas fires. If you are a homeowner considering a gas stove and you have no chimney or flue, a balanced flue appliance is likely the first option an expert will suggest. Just remember that balanced flue terminals must be installed to meet clearance requirements, for example, a minimum distance from windows, doors, and neighbouring properties. These rules are detailed in gas safety regulations and BS 5440, and your installer will handle compliance.